AI as an Inventor? . . . Not so Fast

In December, the United Kingdom (the “U.K.”) became the fourth jurisdiction to reach a final determination that a generative AI platform could not be named as an inventor on a patent. Like courts in the United States, Australia and Taiwan before it, the U.K. Supreme Court relied on statutory language to hold that “an inventor within the meaning of the 1977 [U.K. Patent] Act must be a natural person and [the AI] is not a person at all, let alone a natural person.” Thaler v. Comptroller-General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks, [2023] UKSC 49, 14.

In each instance the court was asked to consider a patent presented by Dr. Stephen Thaler as part of his Artificial Inventor Project (the “AIP”) where Dr. Thaler named his AI platform, DABUS, as the sole inventor. Dr. Thaler and AIP have initiated test cases in eighteen jurisdictions around the world seeking intellectual property rights, i.e., patents and copyrights,1 for AI-generated output without a traditional human inventor or creator. According to the AIP, the goal is “to promote dialogue about the social, economic and legal impact of frontier technologies such as AI and to generate stakeholder guidance on the protectability of AI-generated output.”

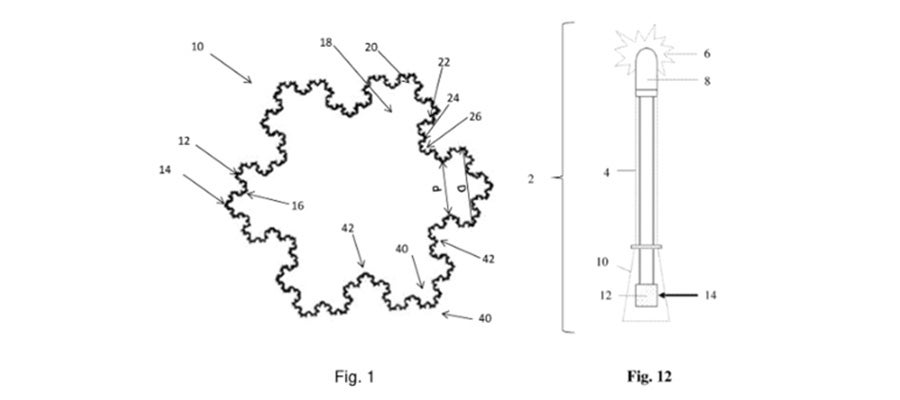

Of the eighteen jurisdictions in which Dr. Thaler has filed patent applications, four have been rejected (U.S., U.K., Australia and Taiwan), five have been rejected pending further judicial review, seven are still in the prosecution stage, one has been allowed, and one has been granted. In each jurisdiction, Thaler filed patent applications on two inventions: one teaching a food container with walls having a fractal profile, and the other an LED lamp device having pulse train “at a frequency and fractal dimension” for “attracting enhanced attention.” In each case Dr. Thaler identified the sole inventor as the AI DABUS.

Figure 1 Fractal Container (Fig. 1) and Neural Flame (Fig. 12) both described in WO2020079499

Like the U.K. Supreme Court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that “[f]or the reasons explained above, the Patent Act, when considered in its entirety, confirms that ‘inventors’ must be human beings.” Thaler v. Vidal, 43 F.4th 1207, 1212 (Fed. Cir. 2022), cert. denied, 143 S. Ct. 1783, 215 L. Ed. 2d 671 (2023). Similarly, in Australia, the Federal Court of Australia reversed the Primary judge and concluded that “having regard to the statutory language, structure and history of the Patents Act, and the policy objectives underlying the legislative scheme, we [hold] . . . . that, by naming DABUS as the inventor, the application did not comply with reg 3.2C(2)(aa).” Commissioner of Patents v. Thaler [2022] FCAFC 62, 31 (cert denied).

Other jurisdictions have different requirements for inventorship and are considering different arguments for dealing with this issue. South Africa, for example, made news in 2021 by becoming the first jurisdiction to grant a patent to an AI when it issued the Thaler patent. However, because patents in South Africa are not subject to the same formalized patent-examination procedure found in other jurisdictions like the U.S. and Europe, this grant may be tested later.

While the Courts reviewing this issue have appropriately focused on statutory language and avoided policy considerations, Congress and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”) have been weighing this issue and considering whether the patent laws should be changed to allow for AI to be named as an inventor. On June 7, 2023, the Senate Subcommittee on Intellectual Property held a hearing featuring a panel of patent law experts. One of the panelists, Prof. Ryan Abbot, who works closely with Dr. Thaler and heads the AIP, testified that he believes the patent laws should be amended to allow AI-generated inventions to be patentable. He explained that, under current law, conception is the hallmark of inventorship. Therefore, if an AI contributes to an invention such that it should be named as an inventor or co-inventor, the invention would be unpatentable because the proper inventors could not be named. The other four panelists, however, expressed their views that U.S. patent laws should not be changed to allow an AI to be an inventor, at least not yet. Prof. John Villasenor from UCLA, for example, articulated the view that AI should be treated like any other tool and that inventorship should be attributed to the persons using the AI. He proposed reconceptualizing conception, which is not defined by statute, to “encompass ideas formed through collaboration between a person and tools that act as extensions of their mind.”

The USPTO has also considered this issue through its AI and Emerging Technology Partnership, which has published Requests for Comments, and held a number of events, including East and West coast “Listening Sessions,” to explore the idea of AI as an inventor and other issues related to AI and patents. During those sessions, some of the speakers advocated for changing the patent laws to accommodate AI as an inventor and raised other issues, such as whether AI generated prior art should be considered prior art and whether the availability of AI should change how we think about the person of ordinary skill in the art when evaluating obviousness.

Why it matters

As AI tools become more ubiquitous, it will be important for developers to remain aware of the relative contributions of AI platforms to any invention. For now, the law in the U.S. is settled that only a human can be named as an inventor. Although the USPTO may not question a patent applicant’s inventorship claims, the details will certainly be exposed in any subsequent litigation, where an accused infringer could try to establish that some or all of the claimed invention was conceived by an AI, potentially rendering the patent invalid. Developers who use AI, therefore, should create and retain records that will enable them to show the degree to which any AI was used and to establish that the inventions claimed were conceived only by humans.

1 Manatt addressed recent developments with AI and copyrights here.