Manatt Health: Health AI Policy Tracker

Introduction

2025 saw a sustained increase in health AI policy activity at federal, state, and self-regulatory levels. What began as a wave of state efforts to study AI and exploratory proposals in prior years has matured into more concrete legislation, regulatory debate, and targeted oversight. Across states and in Washington, policymakers are increasingly focused on nuanced tensions: protecting patients from harm, preserving and encouraging innovation, and defining how—and when—AI should be treated like a traditional health-care tool.

Major Themes from 2025

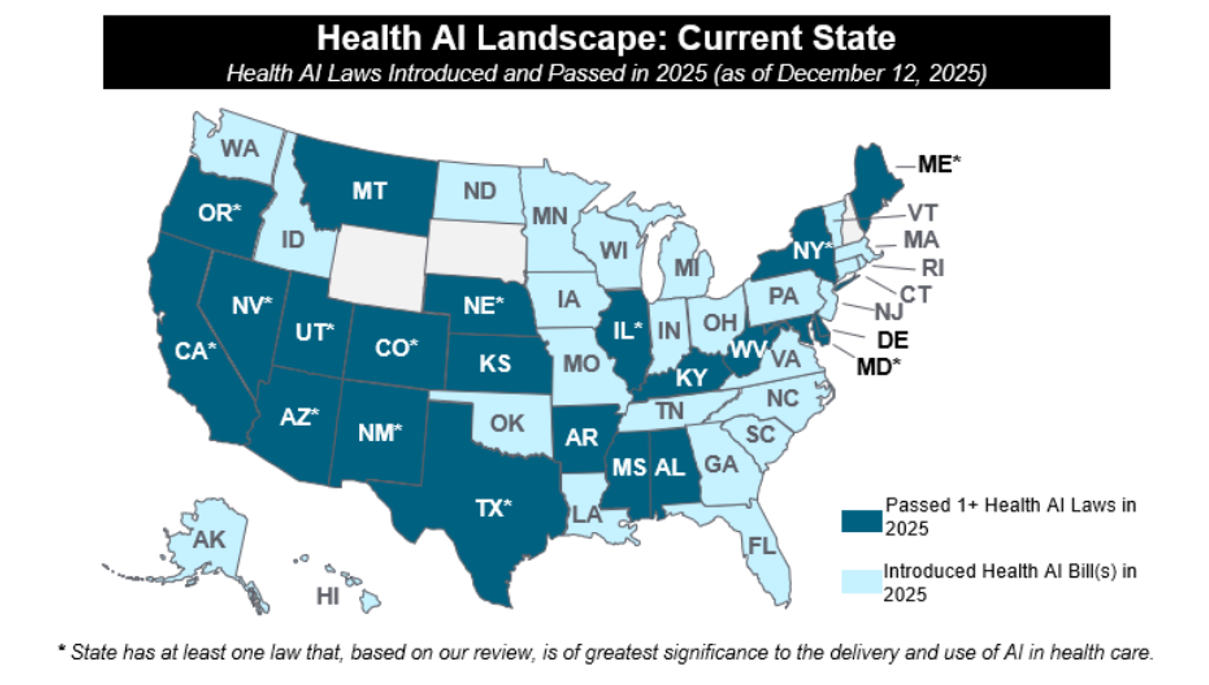

In 2025, forty-seven states have introduced over two hundred and fifty AI bills impacting health care. Thirty-three of those bills were passed and enacted into law in twenty-one states. Key themes in 2025 included heightened attention on AI chatbots (particularly related to mental health); use of AI in clinical care; transparency; payor use of AI; and the emergence of “AI Sandboxes” for testing of innovative AI tools.

In the second quarter of the year, Congress advanced a near-final draft of H.R. 1 (“One Big Beautiful Bill”) that included language that would have barred state or local enforcement of laws or regulations on AI models or systems got up to ten years. After significant bipartisan pushback from the states, this moratorium was not enacted – but served as a signal of bipartisan interest in regulating AI deployment to protect consumers, and especially children. The enacted version of H.R.1 included the Rural Health Transformation Fund, which focuses on investment in technology platforms that enhance care delivery, particularly those that are consumer-facing, such as remote monitoring tools, telehealth, and AI-enabled systems (see Manatt on Health summary ).

While Congress has not passed any laws directly regulating AI, this year saw significant federal action from the administrative branch in the form of numerous Executive Orders (EO) and the release of the . Most recently, on December 11, President Trump issued an (EO) directing federal agencies to take legal and other action, including withholding federal grants when legally permitted, to challenge state laws regulating AI that it views as overly cumbersome or unlawful and calling for the development of a “minimally burdensome” national standard. The EO’s impact on state legislative action remains to be seen; only Congress can preempt state laws, and the Administration may have an uphill battle showing state AI laws violate the Constitutional provisions called out in the EO. States considering new legislation may take into account the risk of litigation by the Attorney General and the withholding of BEAD program or other federal funds in deciding which laws to pass. For further analysis on this EO, see Manatt on Health summary .

Regulatory agencies issued guidance and requests for more information, held hearings, and initiated investigations. Notably, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) took significant action to promote the use of AI in Medicare and Medicaid, including issuing a request for public comment on appropriate payment strategies for software as a service and artificial intelligence as a part of the CY2026 Proposed Medicare Physician Fee Schedule and issuing a seeking public feedback on digital tools (including AI) that can improve Medicare beneficiary access, improve interoperability, and reduce administrative burden. Most recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) launched the Advancing Chronic Care with Effective, Scalable Solutions (ACCESS) Model, a ten-year national voluntary demonstration that incorporates Outcome-Aligned Payments (OAPs) to Medicare Part B reimbursement for chronic condition management. Connected to the launch of the ACCESS model, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published a announcing the Technology-Enabled Meaningful Patient Outcomes (TEMPO) Pilot for digital health devices across the four ACCESS model tracks. While the ACCESS Model is not AI-specific (like the Wasteful and Inappropriate Service Reduction Model (WiSER) model, launched earlier this year) technology companies with AI-enabled digital health tools targeting chronic conditions may participate. Notably, digital health devices must meet the definition of a device under the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act and be intended for clinical supervised outpatient treatment in one of the four ACCESS model focus areas. See Manatt’s summary of the ACCESS model , and the TEMPO Pilot .

Lastly, 2025 saw an increase in guidance and action on the use of AI in health care from self-regulating bodies and other accreditation organization. These organizations in the health care space seek to supplement the patchwork of existing state and federal regulations.

Changes in Priorities: 2024 to 2025

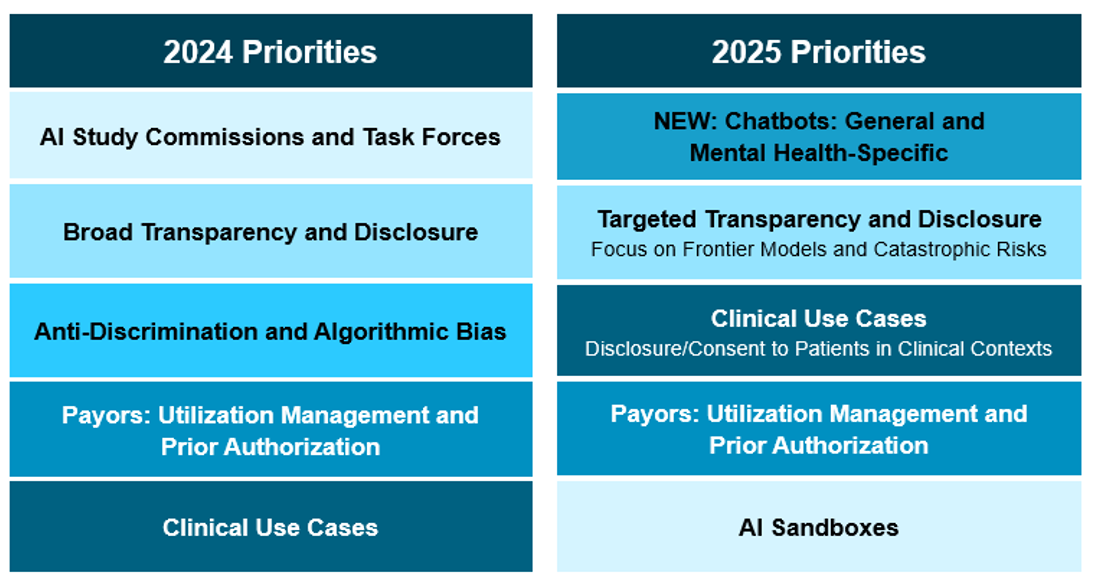

Compared with 2024, policymakers have shifted from broad governance frameworks toward more use-case-specific regulation—particularly in mental-health chatbots, payor algorithms, and high-risk clinical tools. The Sandbox model and consent/disclosure rules have gained traction, while broad anti-bias mandates and omnibus AI legislation (such as Colorado’s ) have lost momentum.

1. AI Chatbots and Mental Health:

The federal government and state legislatures have taken notice of AI chatbots, especially those used for mental health support. States introduced twenty-one bills focused on AI chatbots and passed seven laws focused on AI-enabled chatbots – five of which had a specific mental health focus -- driven by concerns about patient safety.

Earlier this year, Utah issued on how mental health providers should use AI as part of its AI Learning Laboratory program. Utah’s Learning Laboratory is overseen by The Office of Artificial Intelligence Policy, whose stated purpose is to create thoughtful regulatory solutions for AI applications while encouraging innovation and protecting consumers. New Mexico put in place (Section 16.27.18.24, effective November 18, 2025) on the ethical use of AI by counselors, therapists and other mental health providers.

Notably, in October, California enacted (effective January 1, 2026), which establishes requirements for companion chatbots made available to residents of California. The bill includes requirements for “clear and conspicuous notification” indicating a chatbot is artificially generated if not apparent to the user and bans deployment of companion chatbots unless the operator maintains a protocol for preventing the production of suicidal ideation, suicide, or self-harm content, including referral notifications to crisis service providers such as a suicide hotline or crisis text line. SB 243 requires chatbot operators to comply with more stringent requirements if the user is known to be a minor, including disclosing to minors they are interacting with AI, providing periodic reminders that the chatbot is artificially generated and to take a break, and taking steps to prevent sexually explicit responses to minors.

At the federal level, congressional hearings and agency actions focused on mental health chatbots underscores growing concern over their use by youth and individuals with acute behavioral-health needs:

- On September 11th, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) it was launching an enforcement inquiry into AI chatbots acting as companions, coming on the heels of numerous news stories highlighting negative impacts of AI chatbots and companions, particularly on young people engaging with them for mental health support.

- On November 18, the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Oversight and Investigations Subcommittee on the risks and benefits of AI chatbots. The hearing focused significantly on the use of general-use AI chatbots for mental health support and health information.

- On November 6, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s Digital Health Advisory Committee, together with relevant staff, explored market and regulatory perspectives regarding “AI companions,” mental-health chatbots, and clinical decision-support tools.

While oversight of AI chatbots has largely centered on treating them as software, recent academic discussion suggested an alternative approach: licensing AI-enabled medical tools as advanced clinical practitioners rather than relying solely on FDA regulation. As state and federal policymakers turn increased attention to AI-enabled chatbots in 2026, it remains to be seen whether any jurisdictions will explore or pilot this model.

2. AI Use in Clinical Care:

States focused on legislating AI use by healthcare stakeholders and requiring that patients are aware that such tools are being used. In August, Illinois Governor Pritzker signed (effective August 1, 2025), a far-reaching law, which prohibits the use of AI systems in therapy or psychotherapy to make independent therapeutic decisions, directly interact with clients in any form of therapeutic communication, or generate treatment plans without the review and approval of a licensed professional. The law additionally forbids AI chatbots from representing themselves as licensed mental health professionals. Notably, physicians are not subject to this law.

Several states across the political spectrum are attempting to follow Illinois’ footsteps. For instance, Ohio’s (introduced in November 2025) prohibits the use of AI to make independent therapeutic decision or diagnosis or directly interact with a client; it also prohibits use of AI to detect emotional or mental states. Florida’s , pre-filed for the 2026 legislative session, mandates that most mental health practitioners do not use AI other than to performed administrative tasks, and stipulates that mental health practitioners may only use AI to transcribe therapy sessions if they obtain written, informed consent from the patient at least 24 hours in advance.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has also shown interest in AI-enabled medical devices: in late September, FTC issued a on measuring and evaluating the performance of AI-enabled medical devices.

3. Patient Consent and Disclosure

There has been an increasing interest in disclosing use of AI to patients and/or requiring their consent for use:

- Illinois (passed, as discussed above) also requires that any licensed professional using AI tools inform the patient or their legal representative of the use and purpose of the AI and obtain consent. The consent requirement is not met by requiring a patient to accept a broad terms of use or general consent; the law suggest it may need to be standalone consent.

- Texas (enacted June 22, 2025 and effective January 1, 2026), requires that a health care provider must provide written disclosure to the patient that an AI system is being used in connection with health-care services or treatments prior to or on the date of service (except in emergencies), with additional obligations placed on state agencies and non-governmental AI deployers and developers to provide clear and conspicuous disclosure to consumers.

- Ohio’s (introduced in November 2025 and discussed above) also would require a patient to provide written informed consent regarding the use of AI.

- Pennsylvania’s (also introduced in November 2025) would require licensed facilities and healthcare providers to, among other things requiring disclaimers when AI is used to generate clinical communications and disclose when AI algorithms are used in clinical decision making.

- As noted above, Florida’s (pre-filed for 2026 legislative session) requires written, informed consent at least 24 hours in advance of any AI system recording or transcribing a counseling or therapy session.

- New Mexico’s (discussed above) requires counselors, therapists and other mental health practitioners share information on AI tools with patients (including information on the intended use, purpose, and risks of the AI system) and obtain informed consent before using AI tools.

As described above, FDA recently launched the TEMPO Pilot in connection with the CMMI ACCESS Model. Participants in the ACCESS model that choose to use a device in the TEMPO Pilot are required to obtain enhanced consent from beneficiaries before using the device; the consent must inform them that the device is a part of the TEMPO program and that specific data will be shared with the FDA, as required by federal privacy and security laws.

While most of the state laws have not yet passed, we believe this will be a continued area of activity in 2026.

4. Transparency, Disclosure, and Retraction From Broad Governance Frameworks

The start of 2025 saw sustained enthusiasm for sweeping, comprehensive AI-governance frameworks, following the passage of Colorado , a consumer-protection statute that imposes extensive requirements on developers and deployers of “high-risk” AI systems (including health care stakeholders, unless exempted). However, by year-end, states shifted toward more narrowly targeted disclosure obligations anchored in clinical or patient-facing use cases (as discussed above).

When Governor Polis signed SB 205 in May 2024, he noted significant reservations and requested the General Assembly amend the law to address concerns. In 2025, undeterred by Governor Polis’ commentary, nearly twenty states introduced bills heavily modeled on SB 205. Virginia’s was the first to reach a governor’s desk in March 2025, where it was vetoed by Governor Glenn Youngkin. Governor Youngkin provided his veto rationale via a to the legislature, including that HB 2094 would “establish a burdensome artificial intelligence regulatory framework” that would inhibit economic growth in the state – especially for startups and small businesses – and could not adapt to the “rapidly evolving” AI industry. Governor Youngkin’s letter is reflective of strong industry pushback on HB 2094. After Governor Youngkin’s veto, bills modeled on Colorado’s SB 205 did not advance significantly in other states.

In Colorado, lawmakers attempted but failed to advance major changes in response to Governor Polis’ request during their regular session. Ultimately, during Colorado’s August 2025 special session, the legislature passed , delaying SB 205’s effective date from February 1, 2026 to June 30, 2026 to allow time for additional changes.

One state successfully passed its own broad transparency law in late 2025: California’s (enacted September 29, 2025; effective January 1, 2026). Diverging from the Colorado approach, California’s law is only applicable to “large frontier developers.” This law requires such developers to write, implement, comply with, and publish frameworks applicable to their frontier AI models that include details on how developers incorporate national, international, and industry-consensus best practices into model development and how developers identify and mitigate against the potential for catastrophic risk, as well as descriptions of cybersecurity practices, internal governance practices, and processes to report critical safety incidents. The law also requires large frontier developers to publish transparency reports and establishes whistleblower protections for employees that are “responsible for assessing, managing, or addressing risk of critical safety incidents.” At this time, this law may have limited impact on health care stakeholders use of AI.

Collectively, these developments demonstrate a policy recalibration: Colorado illustrates the difficulties of implementing expansive, cross-sector AI oversight; the rise of clinically tailored transparency and consent requirements demonstrates where policymakers see the most immediate need for guardrails—namely, direct patient interactions, clinical decision-making, and health-system operations.

5. AI Sandboxes and Innovation Pathways

In 2024, Utah passed , which included the creation of a state Office of Artificial Intelligence Policy (OAIP) to oversee a “regulatory learning laboratory” and enter into temporary regulatory mitigation agreements with learning laboratory participants to waive specific legal and regulatory requirements set forth by the state. As of December 2025, has launched the Learning Lab and entered into two (both for clinical use cases: dental hygienist and mental health for school children).

In 2025, other states began introducing frameworks designed to allow controlled testing of AI tools prior to full deployment that exempt them from existing law and regulation, often called AI sandboxes. Two states enacted AI regulatory sandbox programs in 2025:

- Texas: establishes an AI regulatory sandbox program that enables “legal protection and limited access to the market” in Texas for the purposes of testing “innovative artificial intelligence systems without obtaining a license, registration, or other regulatory authorization.” Program participants must obtain approval from the Texas Department of Information Resources via an application. Program participation is for a duration of 36 months, with extensions per the discretion of the department; participants must submit quarterly reports to the department summarizing performance. The state’s attorney general is prohibited from filing or pursuing charges against a program participant for any laws or regulations waived during the testing period.

- Delaware: directs the Delaware Artificial Intelligence Commission to collaborate with the Secretary of State to establish an AI “regulatory sandbox framework for the testing of innovative and novel technologies that utilize agentic artificial intelligence” and submit a written report of the findings and recommendations to members of state government, including the governor.

Three additional states introduced, but did not pass, AI Sandbox programs in 2025 (Oklahoma , Pennsylvania , and Virginia ).

On September 10th, 2025, Senator Cruz (R–Texas) introduced the Strengthening Artificial Intelligence Normalization and Diffusion by Oversight and eXperimentation (SANDBOX) Act. The SANDBOX Act would mandate the director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to create a “regulatory sandbox program” within one year of enactment. While this bill has not progressed, we will track it closely in 2026. Under the proposed SANDBOX Act, through a formal process, companies developing AI tools may request waivers from federal regulations for an initial period of two years, renewable up to four times for a total of one decade of exemption from federal regulations. Applicants must demonstrate consumer benefits, operational efficiency, economic opportunity, job creation, and advancement of AI innovation, while showing that benefits outweigh health and safety risks. Waivers apply only to regulations, not statutory laws, criminal liability, or consumer rights to sue. Companies granted waivers must publicly disclose participation details, testing status, risks, liability clarifications, timelines, and complaint channels, and report incidents involving harm within 72 hours. They must also submit periodic reports on consumer participation, risk assessments, and waiver benefits at specified intervals. Supporters argue the Act fosters innovation while preserving core protections; critics contend it shifts risk to the public and reduces accountability.

6. Payor Use of AI for Utilization Management and Prior Authorization

The pace of legislative activity around payor use of AI slowed over the course of 2025. In 2025, states introduced approximately 60 bills aimed at regulating AI use by insurers, managed care plans, or other payors—of those, four were enacted into law (Arizona , Maryland , Nebraska , and Texas ). Themes across those bills were consistent: prohibiting the sole use of AI to deny care or prior authorizations, requiring human review of algorithm-driven decisions, and mandating clear disclosure when algorithmic systems are used in claim or coverage decisions. While volume declined in latter months of 2025, interest in setting policy and oversight of payor use of AI tools remains. In October, Pennsylvania introduced , setting requirements for health insurer (with some exceptions) use of AI and mandating that a human health care provider review decisions and exercise independent judgment prior to any denial, reduction, or termination of benefits, including prior authorization. The bill further requires insurers to disclose use of AI in utilization review; publicly post information on use of AI in utilization review on their web site; periodically review performance, use, and outcomes of AI algorithms; and submit compliance statements to the Department of Insurance annually.

In 2025, there has not been significant federal focus on payor use of AI, except for its use to address fraud and abuse in the Medicare program. The most significant action to date is CMMI’s June launch of the WiSER Model . Under WiSER, CMS will partner with technology companies to provide use AI to “improv[e] and expedit[e]” prior authorization process compared to Original Medicare’s existing processes to reduce fraud for several services/products.

We will continue to monitor this area in 2026.

Looking Ahead to 2026

As health systems, payors, and technology developers continue to integrate AI into clinical and operational workflows, 2026 is poised to be another pivotal year for AI policy in health care. Key issues to watch include:

- Federal efforts to preempt state laws through executive orders, administrative rules, and legislation.

- Both heightened interest in and scrutiny of general-use AI chatbots deployed as companions or for mental health support, with states beginning to align on more targeted legislative language that provides pathways for adoption while mitigating some of the most harmful risks.

- Continued initiatives by CMS and FDA to promote AI adoption through pilot programs, reimbursement model proposals, and regulatory guidance – including more details on the ACCESS model.

- Growing interest in regulatory sandboxes at both federal and state levels to foster innovation while managing risk.

- Emerging clinical use cases driving state legislation and board regulations—physician and nurse adoption may be next on the agenda.

- Ongoing debate over patient consent and disclosure requirements before AI is used to augment care, and the general usefulness of consent/disclosure as a construct for AI tools.

- Colorado’s next move on its Transparency and Anti-Discrimination Law—will lawmakers pursue amendments or further delay implementation?

Deep Dive: State Activity

For a full list of all laws prior to and including 2025, please see .

Deep Dive: Self-Regulating Body Activity

- September 2025: the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission (URAC) released two new accreditation tracks for AI – one intended for and one for in clinical and administrative settings. The accreditation requirements for both tracks focus on security and governance processes and were developed by an advisory council composed of representatives from health, technology and pharmaceutical organizations.

- September 2025: Joint Commission, the oldest national health care accreditation organization, released in partnership with the Coalition for Health AI (CHAI), the largest convener of health organizations on the topic of AI. The guidance focused on the responsible use of AI in healthcare, with an emphasis on promoting transparency, ensuring data security and creating pathways for confidential reporting of AI safety incidents. Among other recommendations, Joint Commission and CHAI specifically recommend that health care organizations implement a process for the voluntary, confidential and blinded reporting of AI safety incidents. Looking forward, Joint Commission and CHAI state they plan to leverage stakeholder feedback on the guidance to develop “Responsible Use of AI” Playbooks and Joint Commission will establish a “Responsible Use of AI” certification program based upon the playbooks. We will continue to track the collaboration between Joint Commission and CHAI .

- The National Committee for Quality Assurance launched an in July to explore standards for responsible governance in health care and announced it was considering a potential “AI Evaluation” offering, which if approved, is expected to launch in the first half of 2026.

Deep Dive: Federal Activity:

2025 Activity To-Date | |

|---|---|

White House |

|

Congress |

Several others that touch on AI in health care and which we will report on if they gain traction. |

FTC |

|

HHS Appointments and Announcements |

|

OCR |

|

ONC |

|

CMS |

|

FDA |

|

NIH | In June 2025, NIH requested public comment to inform an institute-wide AI strategy (public comment page no longer available). |

DOJ | Litigation continues over alleged use of AI to deny Medicare Advantage claims. In June 2025, DOJ against over 300 defendants for participation in health care fraud schemes, with a parallel announcement from CMS on the successful prevention of $4 billion in payments for false and fraudulent claims. |

For questions on the above, please reach out to or . A full list of tracked bills (introduced and passed) from 2024 and 2025—classified by topic category and stakeholder impacted—is available to Manatt on Health subscribers; for more information on how to subscribe to Manatt on Health, please reach out to BJefferds@manatt.com. subscribers; for more information on how to subscribe to Manatt on Health, please reach out to .

In 2025, eight bills passed and were signed into law legislating AI-enabled chatbots. Of those, five directly address the use of chatbots in the delivery of mental health services (Utah , New York [New York’s budget bill], Nevada , California , and Illinois ). Two additional laws that passed that address concerns about misrepresentation of chatbots as humans (Maine and Utah ). California’s legislature additionally passed , but the Governor vetoed it in early October. If enacted, AB 1064 would have significantly reshaped how minors in the state interact with AI companion chatbots, as it prohibited operators from making a companion chatbot that is “foreseeably capable” of causing harm (defined broadly) available to anyone under the age of 18. In his , Governor Newsom notes that the “broad restrictions” proposed by AB 1064 may “unintentionally lead to a total ban on the use of these products by minors,” and indicates interest in developing a bill during the 2026 legislative session that builds upon the framework established by SB 243.

Bressman, Eric, et al. “Software as a Medical Practitioner—Is It Time to License Artificial Intelligence?” JAMA Internal Medicine, Nov. 2025. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2025.6132.

Rittenberg, Eve, et al. “Applying Clinical Licensure Principles to Artificial Intelligence.” JAMA Internal Medicine, Nov. 2025. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2025.6135.

See Manatt’s full explanation of this law .

See from NetChoice (an online business trade association focused on free expression and enterprise); from center-right think tank R Street Institute; , , and from the Chamber of Progress (a technology industry coalition); and from the Center for Data Innovation (a think tank for science and technology policy).

“Frontier developer” is defined as a person who has trained, or initiated the training of, a frontier model, with respect to which the person has used, or intends to use a computing power of greater than 10^26 integer or floating-point operations, including computing for the original training run and for any subsequent fine-tuning, reinforcement learning, or other material modifications the developer applies to a preceding foundation model. “Large frontier developer” is defined as a frontier developer that together with its affiliates collectively had annual gross revenues in excess of five hundred million dollars ($500,000,000) in the preceding calendar year.

Catastrophic risk” is defined as a “foreseeable and material risk that a frontier developer’s development, storage, use, or deployment of a frontier model will materially contribute to the death of, or serious injury to, more than 50 people or more than one billion dollars in damage to, or loss of, property arising from a single incident involving 1) a frontier model providing expert-level assistance in the creation or release of a chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear weapon, 2) engaging in conduct with no meaningful human oversight, intervention, or supervision that is either a cyberattack or, if the conduct had been committed by a human, would constitute the crime of murder, assault, extortion, or theft, including theft by false pretense, or 3) evading the control of its frontier developer or user.

“Critical safety incidents” are defined as 1) unauthorized access to, modification of, or exfiltration of, the model weights of a frontier model that results in death or bodily injury; (2) harm resulting from the materialization of a catastrophic risk; 3) loss of control of a frontier model causing death or bodily injury or 4) a frontier model that uses deceptive techniques against the frontier developer to subvert the controls or monitoring of its frontier developer outside of the context of an evaluation designed to elicit this behavior and in a manner that demonstrates materially increased catastrophic risk.

For more detailed information, please see “Utah Enacts First AI Law – A Potential Blueprint for Other States, Significant Impact on Health Care” on Manatt on Health Note that in March 2025, Utah enacted SB 226 (effective 5/7/2025), which repealed SB 149 disclosure requirements and replaced them with similar disclosure requirements required in more narrow scenarios.

The Delaware Artificial Intelligence Commission was established by HB 333 in 2024.

Exceptions include Medicare supplemental insurance; TRICARE policies; and Medicare Advantage or CHIP managed care plans.