Rural Health Transformation Fund: Opportunities to Promote Health Through Nutrition

Overview

As states across the country prepare their applications for the $50 billion , the Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) provides meaningful opportunities to advance health through food and nutrition. State applications are due November 5, with awards expected by December 31. Funding will be distributed over five years beginning in 2026, with $25 billion allocated equally across all states with approved applications and the remaining $25 billion distributed based on 23 technical scoring factors. The NOFO emphasizes “prevention and chronic disease management” and calls for evidence-based interventions that address the root causes of poor health outcomes in rural communities, including nutrition-focused strategies.

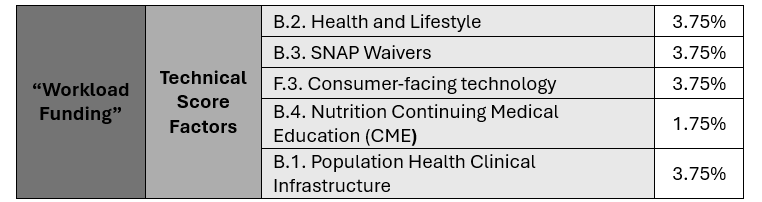

As outlined in the table below, five scoring factors provide some of the clearest opportunities to bolster states’ health-related food and nutrition goals, representing 16.75% of the technical scoring factors. Examples of initiatives that could support these factors are provided below.

Table 1. A Snapshot of Technical Score Weighting for Nutrition and Food Opportunities

Technical Score Factors

Health and Lifestyle

The health and lifestyle factor may provide the greatest opportunity for crafting targeted and cost-effective food and nutrition investments that address chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes and others. The range of options to consider could include:

- Improvements in school food: States may develop enhanced nutrition standards for schools, connect schools to local agriculture through farm-to-school programs, develop improved procurement channels and/or host convenings for stakeholders to develop stronger visions related to child nutrition. Investments in capital infrastructure and training could be targeted to rural schools.

- Promoting local food: Efforts to facilitate access to local, unprocessed foods by low-income rural families provide dietary benefits and support local communities. Approaches may include consumer focused efforts, such as farmers markets, community supported agriculture and community gardens, and those targeting the supply chain, such as food hubs.

- Support for nutrition-oriented charitable and faith-based efforts. Food banks and food pantries can play a significant role in supporting improved nutrition, though the quality of donated and distributed food varies. Nutrition-forward efforts could include support for such rural food providers to adopt nutrition goals and standards for overall offerings and development of wholesome and nutritionally balanced food packages for recipients.

- Developing public-private partnerships with key stakeholders (such as food retailers) to support or facilitate the provision of wholesome food.

SNAP Waivers

States who are pursuing the RHT’s policy objective of restricting purchase of certain foods may also wish to consider including initiatives which emphasize positive nutrition support through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). This could include potential investments in:

- Promoting/expanding SNAP incentives for healthy foods: Most states have existing incentive projects for produce and several states have incentives for dairy products. States could include modest investments in additional projects in rural communities with RHT funds and/or through partnerships. Partnerships with local retailers serving high need communities may be particularly appropriate and offer significant operational flexibility. States could also consider whether existing funded programs can be made more effective with modest investments in promoting these programs to Medicaid participants.

- Community-Level Nutrition Education/Promotion: SNAP funding for hands-on food and nutrition education (i.e., food preparation classes and physical activity initiatives by schools, community groups and Cooperative Extension programs) was recently eliminated. States could consider including the most successful of these programs in targeted rural areas as part of their plans, consistent with the MAHA strategy reports call for community-level transformation.

Consumer-Facing Technology

While the NOFO contemplates consumer-facing technology largely from the standpoint of virtual rural care, states can consider whether platforms integrating across benefits and services, including nutrition, could be useful. For example:

- Self-management consumer apps. In line with the Administration’s emphasis on “health wearables”, states may consider apps that support nutrition tracking and planning, health coaching and other supports that focus on preventing or managing chronic disease.

- SNAP/WIC mobile apps. States could develop processes to improve consumer-facing tools for SNAP, the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program and other supplemental benefits. Client management tools and WIC/SNAP shopping apps can help consumers identify healthy WIC and SNAP eligible foods in their state and expand access to rural communities.

- Cross-benefit apps. Innovators in the consumer-facing tools space are taking strides to integrate Medicaid, SNAP and WIC benefits in a cohesive way. States can prioritize innovative new approaches to better serve rural populations.

Nutrition CME

Prior to and in the wake of Secretary Kennedy’s August 2025 announcement calling for increased nutrition education requirements across all stages of medical education, several states have taken action in this space. For years, accrediting organizations have had discussions related to incorporating nutrition education into practice. In June, passed a law making state funding to medical schools contingent on nutrition education requirements and requiring continuing nutrition training for physician license renewals; also passed a continuing education law requiring physicians to receive one hour of nutrition training every four years. States considering action in this space may also explore developing a process for including nutrition questions in state licensing exams and ensuring that requirements are tailored to specialties.

Population health clinical infrastructure

While this category is quite broad and mentions “other social health services”, it does not explicitly mention nutrition; however, integrating nutrition into the clinical health infrastructure is an evidence-based way to address population health needs and focus on upstream interventions to mitigate or prevent disease. One significant initiative could be to assist rural physicians to operationally integrate medical care and complementary processes for identifying which of their patients are eligible for SNAP, WIC and other existing nutrition support resources (e.g., through integrated data sharing processes).

Conclusion

With a short runway and the clock ticking, states will be balancing their application choices against the NOFO guidance, the evidence base supporting the interventions and their ability to successfully implement with the resources and within the timelines given. Within those guardrails, however, these and other nutrition-focused initiatives could be impactful in both supporting RHT goals and help spark new or fuel existing innovation that address the unique health and nutrition needs of rural communities.

Investing in facility upgrades, minor renovations, and equipment to ensure sustainable operations is permissible, but states may not spend more than 20% of the funding they receive on Capital Expenditures in each budget period. The NOFO is explicit on unallowable costs (e.g., new construction) and states should carefully consider those guardrails.