Response to Request for Quote Held Commercial Offer for Sale, and Invention Invalid

In Junker v. Medical Components, Inc.,1 the Federal Circuit held that a catheter insertion design patent was invalid because the claimed design was offered for sale more than a year before the design patent application was filed. In particular, a letter was sent that included pricing information, payment terms, shipping conditions and bulk pricing options, which the court held are typical of commercial contracts.

Larry G. Junker was the named inventor and owner of U.S. Design Patent No. D450,839 (D’839 patent). Junker sued Medical Components, Inc., and Martech Medical Products, Inc. (“MedComp”), for infringement of the D’839 patent. The parties filed cross-motions for summary judgment arguing over whether a letter Junker sent was a commercial offer for sale of the claimed design, invalidating the D’839 patent via the on-sale bar under 35 U.S.C. § 102(b). The district court awarded Mr. Junker summary judgment of no invalidity under the on-sale bar, and MedComp appealed.

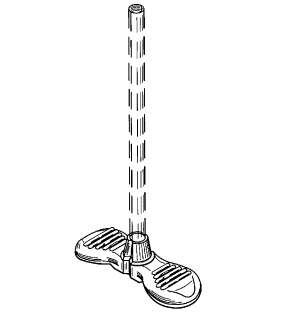

On appeal, the Federal Circuit sided with MedComp that Junker’s pre-critical date letter was a commercial offer for sale, and held the D’839 patent invalid. The D’839 patent, titled “Handle for Introducer Sheath,” included a single claim for “[t]he ornamental design for a handle for introducer sheath, as shown and described.”2 Figure 1 is an illustration of a perspective view of the claimed design (represented with solid lines):

Mr. Junker filed the application that matured into the D’839 patent on February 7, 2000. Hence, the critical date for examining the on-sale bar under § 102(b) was February 7, 1999, i.e., one year before the filing date. Mr. Junker established a work relationship with James Eddings, the founder of a medical device company called Galt Medical. In September 1998, Mr. Eddings notified Mr. Junker that Galt could produce Mr. Junker’s product.

In January 1999, Mr. Eddings’ company, Xentek, produced and supplied Mr. Junker with a prototype of the product that included all of the features of the design in the D’839 patent. Also in early January 1999, Mr. Eddings, through Xentek, began a discussion with Boston Scientific Corp. about providing a peelable introducer sheath product. On January 8, Xentek sent Boston Scientific a letter specifying bulk pricing for variously sized peelable introducer sheath products. The letter stated:

Thank you for the opportunity to provide this quotation for the Medi-Tech Peelable Sheath Set. When we first received this request for quotation we were under the mistaken impression that you wanted the exact configuration as the drawing that was provided which would have required extensive tooling expense. Subsequently, we have learned that this is not the case and are pleased to submit this quotation for a product of our design.

. . .

The principals of Xentek Medical have extensive experience in the design, development and manufacture of this type of medical device. If you should have any specific dimensional requirements this product could generally be tailored to your specifications.3

The letter also included a price chart and indicated that the “prices are for shipment in bulk, non-sterile, FOB [free on board] Athens, Texas on a net 30-day basis.” Mr. Eddings ended the letter by expressing his appreciation for the chance to furnish the quotation and noting that he looked forward to discussing Boston Scientific’s specifications in person.

In 2013, Mr. Junker sued MedComp, alleging four of MedComp’s products infringed the claimed design. MedComp, in response, argued the claimed design is invalid, unenforceable and not infringed.

The district court held that the letter from Xentek to Boston Scientific was not a commercial offer for sale of a product embodying the claimed design, just a preliminary negotiation. The court pointed to the letter’s use of the word “quotation” and its invitation to further discuss terms.

MedComp appealed, and the Federal Circuit reversed. The Federal Circuit explained that a patent claim is invalid under § 102(b) if “the invention was . . . on sale in this country, more than one year prior to the date of the application for patent in the United States.”4 Section 102(b)’s on-sale bar is triggered if, before the critical date, the claimed invention was both (1) the subject of a commercial offer for sale and (2) ready for patenting, the court said.5

The Federal Circuit called the question before it “a simple one: Whether the January 8, 1999 letter is a commercial offer for sale of the claimed design, or merely a quotation signaling the parties were engaged in preliminary negotiations.”6

It held that the letter is a commercial offer for sale of the claimed design:

In making this determination, we look to the specific facts and circumstances presented in this case, applying traditional contract law principles along the way. . . . Only an offer which rises to the level of a commercial offer for sale, one which the other party could make into a binding contract by simple acceptance (assuming consideration), constitutes an offer for sale under § 102(b). . . . To help guide our determination of whether a given communication rises to the level of a commercial offer for sale, we often rely on resources such as the Uniform Commercial Code, Restatement (Second) of Contracts, and other similar treatises. . . . In determining whether an offer [has been] made[,] relevant factors include the terms of any previous inquiry, the completeness of the terms of the suggested bargain, and the number of persons to whom a communication is addressed.7

The court pointed to language in the letter that signals it was a specific offer responding to a quotation request from Boston Scientific with typical language for a commercial contract.8 It also specifies different options to purchase its peelable sheath products, the court found.9

The court acknowledged that the letter ends with an invitation to discuss Boston Scientific’s specific requirements, but said “expressing a desire to do business in the future does not negate the commercial character of the transaction then under discussion.”10 The court said the “completeness of the relevant commercial sale terms in the letter itself signals that this letter was not merely an invitation to further negotiate, but rather multiple offers for sale, any one or more of which Boston Scientific could have simply accepted to bind the parties in a contract.”11

The court explained:

Here, . . . the letter—which specifies multiple sized products for sale, different bulk pricing options available for each product, payment terms (net 30-day basis), and delivery terms and conditions (bulk shipment, non-sterile, FOB)—contains all the required elements to qualify as a commercial offer for sale. That is sufficient to invoke § 102(b)’s on-sale bar.12

Mr. Junker asserted that the letter left out crucial contract terms, such as the size of the product and quantity, and therefore, the letter was not a commercial offer that could be a binding contract if accepted. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument and explained:

Under § 102(b), the question is merely whether there is an offer for sale. As explained above, the letter here offers for sale multiple sizes of products with tiered pricing depending on the number of sets desired. That there were multiple offers does not mean that there was no offer to be accepted. And that the letter does not specify the exact amount Boston Scientific desires likewise does not mean that there is no offer to be accepted. Rather, the letter comprises multiple different offers that Boston Scientific could have accepted by simply stating, for example, “We’ll take 5,000 sets of the 4F-6F Medi-Tech Peelable Sheath” or “10,000 sets of the 11F Medi-Tech Peelable Sheath.”13

Mr. Junker also contended that the January 8, 1999 letter was just a price quotation inviting additional negotiations, not a valid offer. The court disagreed, saying that “the terms of the communication must be considered in their entirety to determine whether an offer was intended, or if it was merely an invitation for an offer or further negotiations.”14 Therefore, the court held the details and comprehensiveness of the commercial terms in the letter outweighed Junker’s arguments.

Accordingly, the court agreed with MedComp that the January 8, 1999 letter was a commercial offer for sale of the claimed design. Since the parties acknowledged that the invention was ready for patenting, the court held that the sole claim of the D’839 patent was invalid.

Going Forward:

The decision does not clarify when a price quotation or offer to negotiate will not be considered a commercial offer for sale, because every situation is fact based. The decision reflects the current uncertainty about when a price quotation will be considered a binding offer for sale, triggering the one-year period under the on-sale bar. For example, would there be a difference if the letter stated, “This is not an offer for sale,” even if it also contained payment terms, shipping conditions and bulk pricing options? What if the letter stated, “Final contract terms to be provided based on quantity, availability and timing”?

Because of the confusion surrounding price quotations and whether they trigger the one-year grace period for the on-sale bar, it generally would be prudent to file a provisional or non-provisional patent application within one year of when any price quotation is made, and preferably to file the patent application even before transmitting any price quotations.

Irah Donner is a partner in Manatt’s intellectual property practice and is the author of Patent Prosecution: Law, Practice, and Procedure, Eleventh Edition, and Constructing and Deconstructing Patents, Second Edition, both published by Bloomberg Law.

1 Junker v. Medical Components, Inc., 25 F.4th 1027, 2022 USPQ2d 146, 2022 WL 402132 (Fed. Cir. 2022).

2 Id., 25 F.4th at 1029 (quoting U.S. Patent D450,839 patent, claim).

3 Id., 25 F.4th at 1030.

4 Id., 25 F.4th at 1032 (citing 35 U.S.C. § 102(b)).

5 Id., 25 F.4th at 1032 (citing Pfaff v. Wells Elecs., Inc., 525 U.S. 55, 67-68 (1998)).

6 Id., 25 F.4th at 1032.

7 Id., 25 F.4th at 1032 (quotation marks and citations omitted).

8 Id., 25 F.4th at 1032.

9 Id., 25 F.4th at 1032.

10 Id., 25 F.4th at 1033 (quoting Cargill, Inc. v. Canbra Foods, Ltd., 476 F.3d 1359, 1370, 81 USPQ2d 1705, 1713 (Fed. Cir. 2007)).

11 Id., 25 F.4th at 1033.

12 Id., 25 F.4th at 1034 (citing Cargill, 476 F.3d at 1369, 81 USPQ2d at 1712, and Merck & Cie v. Watson Lab’ys, Inc., 822 F.3d 1347, 1351, 118 USPQ2d 1562, 1566 (Fed. Cir. 2016)).

13 Id., 25 F.4th at 1034.

14 Id., 25 F.4th at 1035.