Special Edition: Key BCRA Policy Concerns

Special Edition: Key BCRA Policy Concerns

By Cindy Mann, Partner | Chiquita Brooks-LaSure, Managing Director | Patricia M. Boozang, Senior Managing Director | Ariel Levin, Manager

Congressional action on repeal and replace took a number of significant turns in the past few days, and next steps still remain uncertain. On Monday evening, Senators Mike Lee (R-UT) and Jerry Moran (R-KS) joined Senators Susan Collins (R-ME) and Rand Paul (R-KY) in opposing the motion to proceed on the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA), stalling the Senate’s opportunity to pass the bill this week as Republicans could only lose two votes on the motion. Though the bill appeared to be stalled indefinitely, Republican Senators began negotiations again on Wednesday night and released slightly revised bill language and a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) score on Thursday.

Republican senators from both the moderate and conservative wings have expressed concerns with the BCRA throughout this process, leading to these complications with passage. The most significant areas of concern among senators and their governors include:

- Loss of coverage and unaffordability;

- Insufficient (and double-counted) stability funding for the individual markets;

- Significant cuts to Medicaid; and

- The Cruz Amendment.

Below we describe each of these concerns in more detail.

Loss of Coverage and Unaffordability. Both CBO scores of the BCRA estimated a substantial loss of health insurance coverage, increasing the uninsured number by 22 million in 2026 compared to current law, including a loss of coverage for 15 million people covered by Medicaid. Loss of coverage was a major issue during the House American Health Care Act (AHCA) debates, leading to public protest and negative press coverage and ultimately a close House vote. With only a million fewer estimated uninsured under the BCRA than the AHCA, the Senate has not been able to claim that their proposal “solves” the coverage issue that followed the bill from the House. In addition, for low-income and older individual market consumers (including the people who would lose Medicaid coverage under the bill), the total cost of healthcare under the BCRA would be unaffordable as a result of the BCRA’s low actuarial value (AV) benchmark plan and expanded age rating variation. In fact, the most recent CBO score found that the deductible for the benchmark plan would be greater than the legal limit on total out-of-pocket spending in 2026, illustrating just how unrealistic these plans will be for most consumers. (For more information on the coverage and affordability issue, see our previous Manatt on Health.)

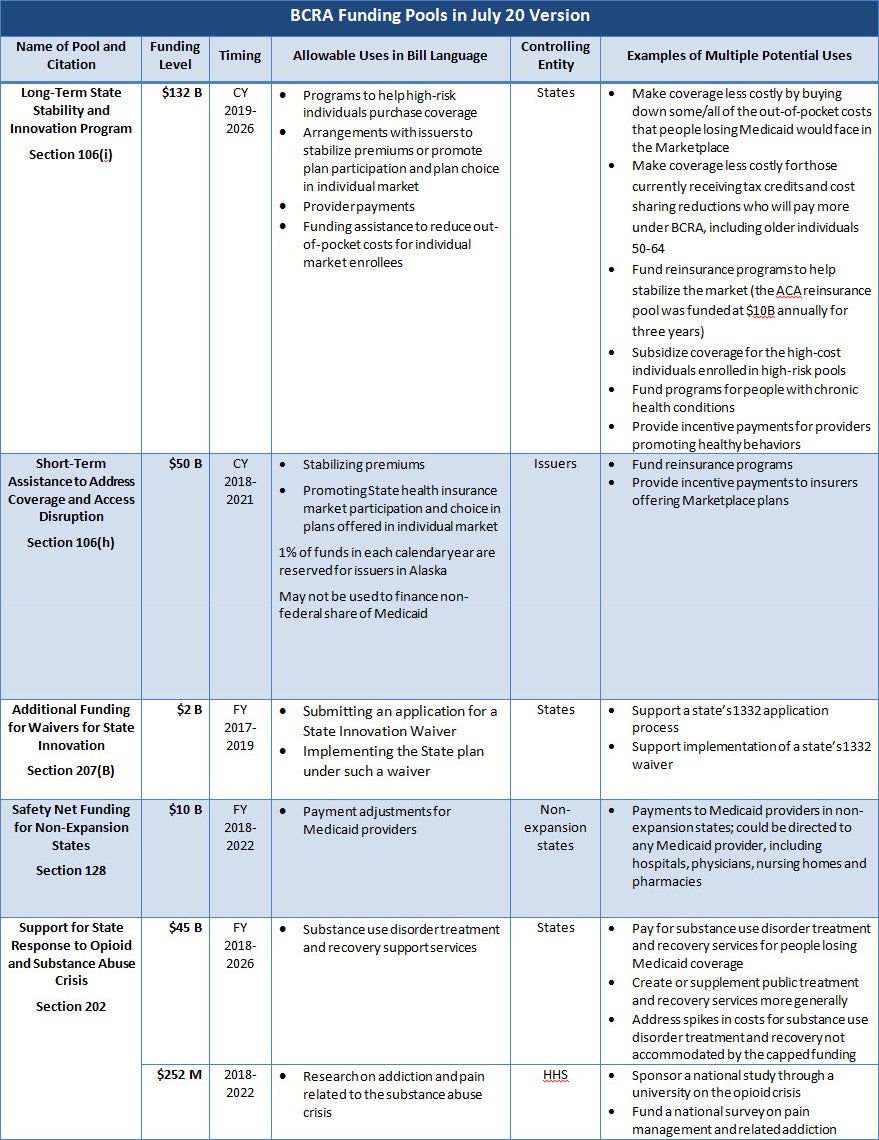

Competing Priorities for Limited Stability Fund Dollars. Like the AHCA, the BCRA included State Stability and Innovation funding intended to help stabilize state individual insurance markets. The July 13 and 20 versions of the BCRA included $50 billion in short-term funding that would go directly to insurers and $132 billion in long-term funding that would go to states ($70 billion more than the original version of the BCRA released on June 26). However, the additional $70 billion was promised for a number of different purposes, including briefly for insurers who chose to offer noncompliant plans under the Cruz amendment (described in more detail below and dropped in the July 20 BCRA version) and to help make coverage more affordable for individuals (a priority for moderates concerned with coverage issues). Still others expected the funding to be used for state reinsurance programs. There were already concerns about the efficacy of the funding to solve any one of these issues; the multiple claims on the funds established to alleviate anxieties across the Republican Caucus only elevated the concerns. See the table below for more information about the funding sources in the BCRA.

Significant cuts to Medicaid. Like the House version of repeal and replace, the BCRA would end the enhanced federal funding for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion; the BCRA would phase out the enhanced match over three years starting in 2021. And like the House bill, the BCRA would limit federal spending through the imposition of per capita caps, with the caps slated to grow by no more than general inflation beginning in 2025. The CBO estimated that the Medicaid provisions in the bill would result in reductions in federal Medicaid spending in excess of $756 billion relative to current law. The cuts to Medicaid funding and the related impact on coverage are among the most controversial and troubling provisions of the BCRA for moderate Republican senators and for governors across the political spectrum. While primary among these concerns is loss of coverage for 15 million people, other issues generated additional, significant opposition:

- The “Cost Shift” to States. The $756 billion in cuts to Medicaid would cause some states to lose more than a third of their federal Medicaid funding. Those reductions would grow over time, and the caps would shift all risks of higher healthcare costs onto states. (See Manatt’s analysis on the financial impact of the BCRA for states.) States would be faced with difficult choices necessary to respond to this level of spending reduction—including eliminating expansion, cutting eligibility and benefits more broadly (e.g., for children, pregnant women, the elderly and people with disabilities), and reducing provider reimbursement, putting access to care at risk—all cause for serious concern among Republican senators and governors including Governor Asa Hutchinson (R-AR), who commented on an earlier version of the Senate plan saying: “We can’t just have a significant cost shift to the states because that’s something we cannot shoulder.”

- The Opioid Crisis. States continue to grapple with the opioid addiction epidemic, and governors and senators in states most impacted by the crisis are deeply worried about the loss of Medicaid expansion funding given the crucial role Medicaid plays in substance use screening, diagnosis, treatment and recovery. The BCRA’s $45 billion fund from 2018 to 2026 to support state grants for substance use treatment did little to assuage these concerns given the time-limited nature of the funding and its likely insufficiency to cover all states’ needs as compared to the current law’s funding for comprehensive coverage through Medicaid expansion. Senator Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV) has been particularly vocal on this issue: “I have serious concerns about how we continue to provide affordable care to those who have benefited from West Virginia’s decision to expand Medicaid, especially in light of the growing opioid crisis. All of the Senate healthcare discussion drafts have failed to address these concerns adequately.”

- Flexibility. From the outset of the repeal and replace debate, Republican governors have been calling for greater flexibility with regard to Medicaid program design and administration. In the July 18 bipartisan governors’ letter to Senate leadership, governors cited “state flexibility” as one of four guiding principles for healthcare reform, and noted their concerns that neither the House nor the Senate’s repeal and replace bill contained any meaningful provisions related to new state flexibility for innovation. In his New York Times op-ed earlier this week, Governor John Kasich (R-OH) said, “[T]he Senate plan was rejected by governors in both parties because of its unsustainable reductions to Medicaid. Cutting these funds without giving states the flexibility to innovate and manage those cuts is a serious blow to states’ fiscal health.”

Cruz Amendment. Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) sponsored an amendment designed to shore up conservative support by allowing insurers that sold ACA-compliant plans to also sell non-compliant plans with limited benefits and medical underwriting. The amendment encountered strong resistance from moderates and stakeholders, including the two leading insurer associations, which said bifurcating the market would make coverage unaffordable for many people with preexisting conditions and called the amendment “unworkable in any form.” In the end, Cruz also lost the support of his co-sponsor, Senator Lee, when Cruz tried to allay other senators’ concerns, including those of Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA), by making the regulated and deregulated business subject to the ACA’s “single risk pool” requirement. Despite Lee’s concerns, there were considerable questions about whether the vastly different types of business could be pooled together in any meaningful sense. Likely in part because the amendment would be so difficult for the CBO to score, the latest version of the BCRA released on July 20 no longer includes this amendment.